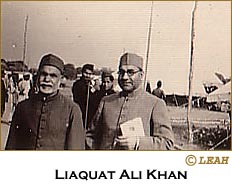

14. Mohammad Ali Jinnah Q: Tell me about Jinnah's human side.  My husband knew more of that because he went and stayed there with Raja Sahib [Mohammed Amir, Raja sahib of Mahmudabad]. He was Raja Sahib's guardian and Raja Sahib was like a son until they had some differences of opinion because Raja Sahib was much more revolutionary against the British than Mr. Jinnah wanted to be, who wanted to be more diplomatic about it and move step-by- step and you know - Q: Cautious? AH: Yes, and take the advantage when it was offered. I saw him the day that he was talking of a direct action day [in 1939] and I saw from the audience lined up all these great men with their titles - British and the others, like Nawabs and Rajas [large landholders] and Sirs - offering them these titles as if he was the headmaster and they were naughty boys at school. I once said to him when I was in my left wing period, why have you got so many Nawabs and people in important positions and he said, well one has to use every means to an end. I also asked him about self-determination, once I remember the Communist Party and everything talking about self-determination, and I say he would always talk about power being at the centre or where and what and where real power would lie. And then he said to me, well of course, it would take time to do all these things because even if you divide a house even if there is a problem in a family or a divorce or anything, it takes time. You can not divide a country with any less thought, which is what made me feel sad afterwards when it was divided without thought really because it [Independence was originally scheduled] to be in 1948, it was made in 1947. Obviously I didn't go into further questions then and my own doubts. We were just sitting at the lunch and I heard that Sonny was going to be sent to. He was by now in the government service, in the supply department, that he was going to be sent as India's Supply Commissioner to England and I was talking rather across the table to Dr. Nazir Ahmad and he said something about England and I said well, yes, I suppose I do want to go. And Mr. Jinnah was sitting, I was on his right ,and he said what did you say? Dr. Nazir Ahmad said, oh, no no she was saying something about joining us [the Pakistan Movement]. You know and he said how very nice I like to have as many soldiers as I can. I am not going to say look I was talking about something else, because as I said I really found him so very nice as a human being. I did not think of him totally as a politician or think of him that I got to have any great argument with him about that. He was kind to me. We went to the Willingdon Club once and I remember when he was sitting there as you know he always liked to - and we were sitting there and one of his Parsi friends said you know Jinnah we should have a leader like you. This is before the things had gathered momentum. He wasn't like those boastful people full of himself. I went to see him and I wished then, I had one of these tape-recorders. He was so human. He was telling me about how - and Miss Jinnah was there with him, she was always with him - and we were sitting there and he said "you know when I first came to Matheran, I came up here and I rang up and said I wanted a room in the hotel and the man who owned it was absolutely in a state of terrible anxiety and said ' you know it is very difficult, I mean we can't give you a room in the main hotel.' " He was laughing and he was saying, it is because the English wouldn't want him [Jinnah] there, you see. So he says 'I can give you room in the cottages' and he was very confident to do that. But he was relating this with absolutely, you know, without any kind of anger or making fun or anything. Tremendous humor when he was narrating the story, how when he was young and he'd gone on like that and I said, good heavens, I am not going back down that hill again. So alright I will be in that cottage and I was looked after terribly well, but that man was so embarrassed that I should turn up and ask for a room. Q: From your sense of talking to him, did he really intend Pakistan as a separate state or was he bargaining for something? AH: I think he bargained in the beginning. I think in the beginning it was bargaining but it became more and more to him an idea that it had to be separated, and there was no other way, I think. He didn't like Gandhiji at all, not at all, he had an anger against him, as if he was a big hypocrite, and that is all he was. I heard him once, say something that was really full of that feeling of dislike. That was shortly after those Gandhi-Jinnah talks in Bombay [in 1940]. My husband as I say knew him better in many ways, and had once told me that it was interesting - once he had asked Mr. Jinnah about his life here [in England], whether he had been fond of dancing. He said I once asked somebody to dance with me and she refused and I never asked anybody ever again. That kind of thing. And then of course I had a Parsi friend who knew his wife [Ruttie Jinnah, a Parsee] , had grown up with her and said that he was remarkably patient and really was fond of her because she was difficult. You know, she said he was very good about that. Also Mrs. Naidu said that I love that man, and he is a lonely man. Q: I think after Ruttie died he really sort of clammed up personally? AH: Yes. And then of course, the only other time there was his personal thing, when only Sonny and I were there with him, with our friend Prem Bhagat, who was the young V.C. [Victoria Cross winner] the first of that Second World War, amongst the Indians. Prem said please take me to see him, I want to ask him why he is saying all that he says? And Prem had just been awarded V.C at a big parade and had it on a ribbon and we walked in and he was in his uniform. And Sonny said I want you to meet our friend, and he didn't complete our fried Prem Bhagat. He just said our friend. And Mr. Jinnah said oh you are in the [Muslim League] National Guard, are you, which made me, of course, want to burst out laughing, because I thought dear Prem.  But Prem said sir I had come to ask you this one thing. I was in the western desert and my life was saved by my soldiers, they were Muslim soldiers, so I don't understand [this division between Hindus and Muslims]. He said my dear young man, if all the Hindus were like Prem Bhagat, perhaps things would be different. Also, I put you into the army, he said, and Prem looked sort of baffled and he said that he had been amongst the first, if not the first to fight for Indianization of the army. But I have never forgotten that first entrance. Q: Tell me about Liaquat [Ali Khan, Pakistan's first Prime Minister] a little bit? AH: I knew him very well. He was a member of the Lucknow Legislative Assembly before all the movements began, and then during and after when he was in the Cabinet. I knew his wife [Begum Rana Liaquat Ali Khan, a prominent social and women's leader in Pakistan] when she was Miss Pant. Q: Oh, when she was Miss Pant? AH: Yes, I knew her then. Q: She was a teacher at that time? AH: She was a teacher. Before he was married he used to come to the house to meet my father-in-law and talk to him. And once when this had begun. the Pakistan cry had begun. I said to him do you know something what is happening is that I am going to cite the Muslim League as the co-respondent when I have my separation from Sonny! All this Pakistan and Hindu - and we were sitting and laughing with him. And nobody would believe it that he said me what you mean Pakistan, what Pakistan? The Hindus have coined it. It was still not a part of the whole movement as a separate state. Not a thought about. This is only when, you know Pakistan with those, who is it, who had written about it? Q: Chaudhry Rehmat Ali in Cambridge [in 1932]. AH: Right. So that at that time it could be said in this light manner. That is why I say for me politics now that I am old and I have seen what has happened - naked imperialism -. now for me there is a despair, and I wish there wasn't, that is why I feel, yes there were eight hundred million people in India, so may be something will emerge out of this black period, that has come. Q: But it just may be too many people for any thing to emerge that can group them all around? AH: Somebody has to. Something has to come out of it unless there is total mayhem, murder. [This interview is from 1991, when relations between India and Pakistan were particularly poor. Improvements in 2004 as this interview is being published speak for the more hopeful note Attia Hosain cherished for the future of the sub-continent. In this respect, The Attia Hosain Trust at Newnham College, Cambridge was set up to fund public lectures on multiculturalism and is presently funding the fees of South Asian women students at the College.] > Images © The Literary Estate of Attia Hosain (LEAH) |

| |

| SOUNDS

| HOME

© Harappa 2004