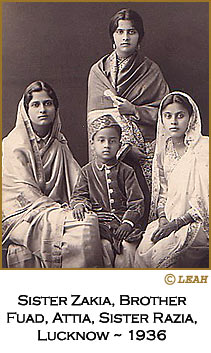

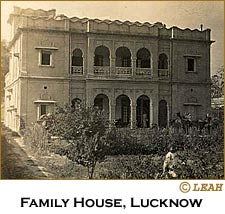

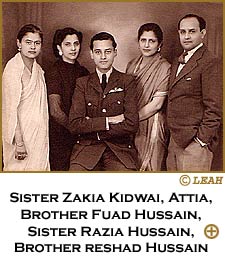

1. Growing Up in Gadia Attia Hosain was interviewed in London on May 19, 1991  QUESTION: Where were you born and where did you grew up? QUESTION: Where were you born and where did you grew up?ATTIA HOSAIN: I was born in Lucknow[in 1913]. I was brought up there. I was educated there. Q: What did your father do? AH: My father [Shahid Hosain Kidwai, ] was a Taluqdar [feudal landholder of Gadia, District Bari Banki, United Provinces]. He was also one of those people who was involved in his life politically a time [in the 1910s] when it wasn't a question of confronting the British as happened later when Gandhiji came on the scene. It was when there were questions in the minds of all the people who were interested in the country's future independence, how to go about it. He was ahead of his time in many ways.  I remember him not as much as I should because he died when I was not quite eleven. He had come to Cambridge, now let us see, it would be the end of the last century. He was about 18 years old and he had come [to England]. He was the only son. He did have a half-brother but he was the Taluqdar himself. He had come to England and briefly gone to Oxford for some reason for a term or so and then went to Cambridge. He was at Christ's [College, Cambridge]. After that he became a Barrister after going to the Middle Temple [UK].

I remember him not as much as I should because he died when I was not quite eleven. He had come to Cambridge, now let us see, it would be the end of the last century. He was about 18 years old and he had come [to England]. He was the only son. He did have a half-brother but he was the Taluqdar himself. He had come to England and briefly gone to Oxford for some reason for a term or so and then went to Cambridge. He was at Christ's [College, Cambridge]. After that he became a Barrister after going to the Middle Temple [UK].

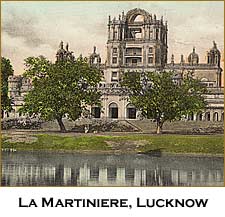

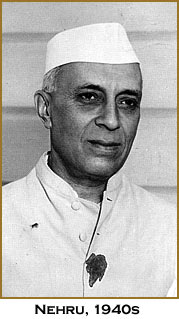

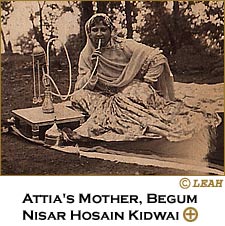

His friends were all people of that time who became very prominent later, north, south, east and west of India because at the time you can imagine there was a different kind of person who came here. They were all finally rather important, or part of the country's history, or fighting for independence. But I remember most of them, as we used to say "uncles" and Mrs. [Sarojini] Naidu [Indian national poet] - not calling her aunt because I never dared to address her. I adored her. But I did know her from when I was very young. Begum Attia Faizi [another prominent artist and intellectual], I knew her from when I was a child. All these people who later on, I now realise, became a part of a historical movement. It is very hard for me to remember names, but Ali Imam, Abbas Ali Baig, Sir Sultan Ahmad, people in Aligarh. Above all my hero was Panditji [Jawaharlal Nehru, India first Prime Minister] father. He was the son of father's friend, Moti Lal Nehru, a very close friend. Therefore I grew up in an atmosphere where people spoke of what to do next, how to be involved, not only in the national movements but in the community, one had to be a part of it. At that time the Taluqdars had a kind of a trade union called the "British-Indian Association." My father was very deeply involved with it. Then my uncles, his cousins who were [brothers] in our forms of relationship, as you know there is no difference between that and really uncles in the sense "Chacha". It didn't matter, first cousins [were like brothers and sisters]. They were also Taluqdars. Gadia [a district in north India's United Provinces, or U.P.] had two Taluqdaries. They [my uncle's family] were one part of it, and my father was the other. Q: And your mother?  AH: My mother came from one of those distinguished intellectual families that belong to a place called Kakori. At that time all those people believed that if you owned land, it led to problems within the family, which alas I know now do exist still. My mother came from that kind of a family where they were proud of being people of learning and became judges, and professionals, that sort of life they had. These great big houses - you can see the ruins of them now because most of the Kakori people seemed to have left and gone to Pakistan. AH: My mother came from one of those distinguished intellectual families that belong to a place called Kakori. At that time all those people believed that if you owned land, it led to problems within the family, which alas I know now do exist still. My mother came from that kind of a family where they were proud of being people of learning and became judges, and professionals, that sort of life they had. These great big houses - you can see the ruins of them now because most of the Kakori people seemed to have left and gone to Pakistan.My mother grew up with that atmosphere around her, so that I was used to having in our home, as we grew up, people who behaved as if they were in salons where poets could sit - the poets being ones own relatives because everybody felt that they had to compose poetry or be interested in classical music or anything that had to do with culture. I was fortunate I had that background. 2. Two Streams of Thought  QUESTION: From childhood? QUESTION: From childhood?(AH): Contacts with the English, I still remember, were also with those same kind of people, naturally. My father's greatest friend was an English man who owned one of the big hotels at the time. He was a barrister. He'd drive to our house with a carriage and pair [of horses], that sort of thing. He spoke the most beautiful Urdu, could recite Persian poetry as everybody did because the classical poetry was always with Persian background. At the same time [I went] to a school which was one of those English schools in Lucknow, the "Martiniere". Q: Oh really, I have seen pictures of the building.  AH: Right. Very few Indian girls went to it because it was meant to be [for Europeans]. [General] Claude Martin [who served the feudal rulers of Lucknow] had left money for educating the domiciled Europeans and the Anglo-Indians and the poor amongst them or their people who needed education. So [he founded] these schools for boys and girls in Lucknow and Calcutta. The parent one [was] in Lyon [France] where he was born. These were really meant for that [Europeans].

AH: Right. Very few Indian girls went to it because it was meant to be [for Europeans]. [General] Claude Martin [who served the feudal rulers of Lucknow] had left money for educating the domiciled Europeans and the Anglo-Indians and the poor amongst them or their people who needed education. So [he founded] these schools for boys and girls in Lucknow and Calcutta. The parent one [was] in Lyon [France] where he was born. These were really meant for that [Europeans].

Q: Not for Indians? AH: Not really, but to get in was a very good thing because the education was very good. So I had that. And then I had at home, moulvis [religious teachers] to teach the Quran, to teach Urdu. I think it is quite unbelievable when people are now talking so much about how can a child learn so many things and how can it do this or that? But we did. Nobody became traumatic about it as far as I can remember. Q: I get the sense that for people like your father the English stream and Indian stream co-existed very well?  AH: Absolutely mixed completely, but that was part of Lucknow. I don't know if it was anywhere else because Lucknow was the centre of culture after Delhi stopped being that [in 1858]. In that town, as I grew, I did not know the difference between religion, caste, who belonged to which part of India? The people who came and settled there, in the university, in the professions of law or teaching or the Taluqdars were from every religion that I can think of, including the Kapurthala part of the family that became Christians. I grew up in a home where we did not have beef cooked, except very rarely, in case a Hindu friend came along. We had lights for Diwali [the Hindu festival of lights]. We had Holi [Hindu spring festival] when our friends came. They came to us for Eid [a Muslim holiday]. AH: Absolutely mixed completely, but that was part of Lucknow. I don't know if it was anywhere else because Lucknow was the centre of culture after Delhi stopped being that [in 1858]. In that town, as I grew, I did not know the difference between religion, caste, who belonged to which part of India? The people who came and settled there, in the university, in the professions of law or teaching or the Taluqdars were from every religion that I can think of, including the Kapurthala part of the family that became Christians. I grew up in a home where we did not have beef cooked, except very rarely, in case a Hindu friend came along. We had lights for Diwali [the Hindu festival of lights]. We had Holi [Hindu spring festival] when our friends came. They came to us for Eid [a Muslim holiday].

Lucknow was like that in those days. I know this that some of our closest Hindu friends. Perhaps we could not go into their kitchens, we could not go near them when they were eating, but it made absolutely no difference to the friendship. That was their life, our life was ours and it came together in friendship. We were together in marriages, at births, deaths, and any festivities. That is why for me all that happens now [the antagonism between Hindus and Muslims] is beyond belief. That is why I think I was already conditioned to believing that faith, in the fact that it can not be that we will be divided because of religion. I couldn't conceive of it myself. Q: It is interesting when you say that your Hindu friends, when they ate, or when they were in their kitchen, you didn't mind not being a part of that. I can understand that. People in the upper classes in general - that never bothered them. But middle class and lower middle class people, they always bring up this kind of an anecdote [to explain Hindu-Muslim tension]. AH: Right. But middle class? What did middle class mean in those early years? There was no great middle class. It did not happen even with them. It did not at that time perhaps because you are talking now much before 1947. Much before 1930 and certain later movements right? It might have infiltrated [later] with politics. That is what always started. If there was a riot, one could put it down definitely to this that somewhere or another, there has been somebody wanting to incite some kind of trouble. For that matter, for heaven sake, there were Shia-Sunni riots [between Muslims]. That would not have been caused by this Hindu-Muslim problem. Q: I understand that [Shia-Sunni riots] was a bigger problem in Lucknow. AH: In Lucknow it quite often happened, but we had relatives who were Shias. We had close relationships. Again now comes that other me that grew up to be politically conscious much more and more as time went on. I always believed that every time [there was a riot], there was a question of "divide and rule" as we thought, yet divide and rule does not mean only an outside power [Britain]. It means anybody who wants power, any ruler. > 3. The Early Muslim League QUESTION: When did you start hearing about Pakistan and the Muslim League?  ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): You must know all about the early years of the development of the Muslim League and the Aga Khan. This kind of feeling [of a separate state for Muslims], I was never conscious of it as being so all pervading as it became, because up to this time [the 1920s and 1930s], it was always a question of the British and how we are going to be free [of them].

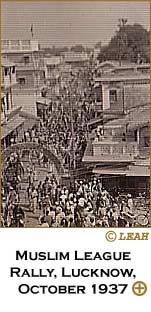

ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): You must know all about the early years of the development of the Muslim League and the Aga Khan. This kind of feeling [of a separate state for Muslims], I was never conscious of it as being so all pervading as it became, because up to this time [the 1920s and 1930s], it was always a question of the British and how we are going to be free [of them]. That was much more important. And one thought, growing up that all those who might talk like the Aga Khan, who was trying to revive the Muslim League, or anybody, it is a certain class of people now trying to do this because they are pro-British. I, from my later teens, or fourteen years old, began to be much more drawn towards the Congress [which stood for an undivided India].  So from now on if you get any kind of slant, it will always be that I was influenced very much by left wing thought and by Panditji's and Gandhiji's movementsbecause I would stand and watch as the processions went by and hear the sound of "Inqillab - Zindabad" [Long live the revolution]. I would hear, because I was friendly with the family, that some of the Nehru family has been hurt during lathi [baton] charges [by the police]. There was then that period of the growth of that idealistic [Swadeshi movement in the 1920s], You heard of people who are giving up everything for the sake of the country whereas here I am sitting. My father had died. My poor mother couldn't obviously do anything beyond bring us up. That was a period when - Q: You worked for Congress from the very beginning?  AH: From the beginning because it stood for something that I felt at time the Muslim League was lacking. It had a background to it, a popular mass background. I mean I witnessed the time when women went out into the streets who had never left their homes before because Gandhiji said so. The burning of clothes that were not woven or made in India, all the Swadeshi [indigenous] things to wear I went to school, this very sort of "God save the King" [institution], I used to go at that time with a sari on that was made of handspun cloth, with what was to become the national flag on the border, all along the border, just to defy everybody there. I normally used to wear dresses but when I had to go to anything [school-related], I'd go and wear that. You see, there was a kind of movement within whole country, of all young people and everybody like that. Everybody I knew including my Muslim relations who were involved in any way politically.

AH: From the beginning because it stood for something that I felt at time the Muslim League was lacking. It had a background to it, a popular mass background. I mean I witnessed the time when women went out into the streets who had never left their homes before because Gandhiji said so. The burning of clothes that were not woven or made in India, all the Swadeshi [indigenous] things to wear I went to school, this very sort of "God save the King" [institution], I used to go at that time with a sari on that was made of handspun cloth, with what was to become the national flag on the border, all along the border, just to defy everybody there. I normally used to wear dresses but when I had to go to anything [school-related], I'd go and wear that. You see, there was a kind of movement within whole country, of all young people and everybody like that. Everybody I knew including my Muslim relations who were involved in any way politically.

Two of those families became prominent in Pakistan later. Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman's was one. His daughter is still in India but the point is every one of us was talking of nothing but independence. How and why and when was another matter. This is after all in the 1930s and coming towards the 1940s later, but in the 1930s and it was inspiring. Even before that, before my father had died, I hadn't really known much about what he used to do or not in this field, I only knew of all these friends and these people who would come to visit us. And Dr. Ansari who had taken a team of doctors to Turkey [during the Khilafat Movement, 1919-1921], all that, was part of one's growing up. So obviously I had to have a political viewpoint. The influences were all left-wing. Two of those families became prominent in Pakistan later. Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman's was one. His daughter is still in India but the point is every one of us was talking of nothing but independence. How and why and when was another matter. This is after all in the 1930s and coming towards the 1940s later, but in the 1930s and it was inspiring. Even before that, before my father had died, I hadn't really known much about what he used to do or not in this field, I only knew of all these friends and these people who would come to visit us. And Dr. Ansari who had taken a team of doctors to Turkey [during the Khilafat Movement, 1919-1921], all that, was part of one's growing up. So obviously I had to have a political viewpoint. The influences were all left-wing.

When I was about fifteen or so, I went to [Isobella Thoburn] college for girls and women, at that time run by Methodists, American Methodists because my mother would never have let me to go to the university where there were men. We were not in pardha in the sense that we were wearing burqas when we went out but we had a confined kind of a life. People who came to visit us in the house were the sons of friends or relations but that was it because my very remarkable mother herself never went anywhere. She had given up everything in life after my father died. But, I would say that [the left wing] influence then came in 1930s from the West. 4. Literature  ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): I had been a voracious reader of books. Alas, I can't read anymore, I can't concentrate but [then] I would read any book that I could lay hands on, fortunately at the time in my father's library, at the school and later at the college. There was then none of this that goes on now, that, "do you teach them Shakespeare or not?" One did learn it. One did learn the classics and read the classics.

ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): I had been a voracious reader of books. Alas, I can't read anymore, I can't concentrate but [then] I would read any book that I could lay hands on, fortunately at the time in my father's library, at the school and later at the college. There was then none of this that goes on now, that, "do you teach them Shakespeare or not?" One did learn it. One did learn the classics and read the classics.

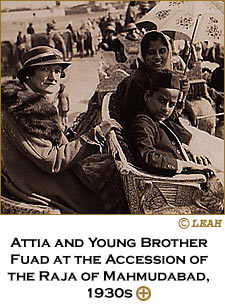

I just loved literature. I had a wonderful teacher when I was at the school. So that apart from all the mathematics or anything, for me it was the books that mattered. And at the time in the 1930s, as you know, from the West came the influence of the Marxist point of view amongst intellectuals. So from here went people, who were like my own relatives. Closest to my father, were two people.  One was Dr. Syeduzzafar from Rampur [a princely state in U.P.], who was the Principal of Medical College and whose nephew is [Sahibzada] Yaqoob Khan [later Pakistani foreign minister]. And the other was Kunwar Bahadur Shah who was like something out of "The Prince," you see, of the Mughals and the Nawabs, in beautiful jamdanis [thin leggings], a kind of 'angharkas.' One was Dr. Syeduzzafar from Rampur [a princely state in U.P.], who was the Principal of Medical College and whose nephew is [Sahibzada] Yaqoob Khan [later Pakistani foreign minister]. And the other was Kunwar Bahadur Shah who was like something out of "The Prince," you see, of the Mughals and the Nawabs, in beautiful jamdanis [thin leggings], a kind of 'angharkas.' A little short, a person from the Hills near Nepal but totally one of those that I told you that for me there was no difference between who was Hindu, who was [Muslim]. My father died and he was a surrogate father. His son, who is alive, thank God to this day, is my brother now that I have lost my brothers because we had been brought up closer than blood brothers and sisters. Dr. Syeduzzafar Khan, a Saeed chacha [uncle] , was like a father to us when we were left [without a father]. My young brother [Air Commodore] Fuad [1928-68],, who became a legend in the Pakistan Air Force was born two months after my father died. So we needed these fathers and uncles and people. My mother certainly needed that support.  These people [like] Saeed Chacha's son Mahmood [Mahmuduzafar, married to Rashida Jan, members of the Communist Party of India] came back from school, from here [England], a Communist like they all were. Sajjad Zaheer [a founder of the Progressive Writer's Movement], all that left wing lot of young men influenced my life but more than anyone Mahmood did. A man who was an idealist, an artist, a writer. He taught me how to read music and understand symphonies. I could play the piano - not too well but knew the theory of music - but not like that. He could read to me a bit of poetry and make it alive because I had never heard poetry in English, recited the way it should have been. At the same time he influenced me politically. So that I believed in the ideal sense in a world that could be created. From every side the influences were there. I did not ever become myself a person joining them because I used to say to Mahmood, you are all dogmatic in many ways. I don't even like my dogmatic Moulvis, so how can I like you? Because in my family by the way it related from the - I don't know which side whether my mother's - but we had these relatives in Farangi Mahal [a school of influential Muslim religious teachers who supported a united India]. Whereas you know Jamal Mian is now in Pakistan, you must know- QUESTION: I have met him. AH: They were the ones who influenced all thought and the Fatwas [religious edicts] and everything for the Sunnis. They were relatives and therefore as you can see the influences [on me] were like that, from all sides. But for me the main influence was that there has to be a world where they will not be injustice. That was when I was an idealist. Q: Religion did not play a part in your political life? AH: No, I believed in my religion but so what? I believed in a religion that to me never said you kill anybody. Never did I believe that religion taught violence because I think I had a very wonderful mother who by the way had set up a madrassah [Muslim religious school]. The first of its kind, where my sister went to teach because when my father died, my sister was taken out of school poor thing. I was young enough to stay on fortunately. She learned with the moulvi [Muslim prayer teacher], my sister did. But she used to go to the school where the girls were taught because my mother said if they are learning the Quran and namaaz [prayer] without understanding, that makes no sense. She had this little school where they were taught the translation [of the Quran] at the same time. These girls [were] from not rich families because there was a Muslim Girls College already existing backed by the Taluqdars and Muslims. They used to study there. It has now become, I believe, a part of a university. My family was like that, and I was taught religion. I think I must have been eight when I fasted for the first time and nobody believed me but I followed all the elders. To me religion was that, it was religion that was, well, drawing everybody together. It was never out of my mind that I was a Muslim. And now today when it is almost as if somebody is slapping you in the face and saying you are a Muslim. I am proud to say 'yes' I am. But please don't distort my religion - anyone, even the Muslims who now do distort it for their own purposes. 5. "Kala Sahibs" [Black Sahibs] QUESTION (Omar Khan): Tell me, in your family and the circle you moved in, who was drawn to the Muslim League and why?  ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): My mother-in-law [Inam Mohammed Habibullah]. She was my aunt, 's mother, Isha'at [Habibullah's] mother, my mother's only sister. My father-in-law took her out of being in the house. My mother had to be, but my mother-in-law, because of her husband, had always been what was called then a progressive person, coming out and meeting people, the British and so on. My father-in-law lived a very British kind of a life. You know like we used to laugh sometimes and say all these "Kala Sahibs" [Black Sahibs]. Very much so. I mean though in my house also, in my home we had these Western and Eastern parts of the house, the Habibullah Household was totally that in a way. My mother-in-law was drawn into public life.

ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): My mother-in-law [Inam Mohammed Habibullah]. She was my aunt, 's mother, Isha'at [Habibullah's] mother, my mother's only sister. My father-in-law took her out of being in the house. My mother had to be, but my mother-in-law, because of her husband, had always been what was called then a progressive person, coming out and meeting people, the British and so on. My father-in-law lived a very British kind of a life. You know like we used to laugh sometimes and say all these "Kala Sahibs" [Black Sahibs]. Very much so. I mean though in my house also, in my home we had these Western and Eastern parts of the house, the Habibullah Household was totally that in a way. My mother-in-law was drawn into public life.  Then when the election time came in 1937, she wanted to be in a Council, the Legislative Council in U.P at the time. She was always inclined towards that because there wasn't the same stream of nationalist [Indian] thought in that part of the family. Q: Even though you are saying they may have been even more British in a way? AH: Yes, but they were more conformist. My father-in-law Shaikh Mohammd Habibullah [Taluqdar of Saidanpur and later Vice-Chancellor of Lucknow University] was not then in the same way as my father had been when he was growing up and influenced us. I mean, I found a letter after my father had died in which he had written about the Jalianwala Bagh incident [in 1919 when hundreds of Indians were massacred by British troops in Amritsar, Punjab] to somebody and mentioned that he talked about it to Pandit Motilal Nehru. This is going to be a turning point in the relationship between the two races. Well, my father-in-law whom I respect greatly, a man of great integrity, was not in that sense involved, [although] he was in the Legislative Council in U.P. When my mother-in-law decided to stand she was a follower of Jinnah, in the sense of the Muslim League. That ideology. She had in her a point of departure from this friendship between the two religions and so on, into being definitely a believer in the Muslim League but never of any violence with each other, but believing that the Muslims had to be like that [separate]. Then my brother-in-law, who was one of the most foremost barristers in Lucknow and later became a High Court judge before he died [joined the Muslim League]. He was brought up in this country. During the time of the First World War he had not been able to go backwards and forwards [between Britain and India] like people did when there were aeroplanes. He grew up here [in England] and went back after he had been at school, at university, at the Middle Temple [Cambridge].  [He was] A Muslim Leaguer but never believed in any Muslims leaving India and going to Pakistan. He said we are fighting for certain rights. We are fighting for certain principles but not as people to leave this country. Organising the Muslims in the same way my husband [later did]. [He was] A Muslim Leaguer but never believed in any Muslims leaving India and going to Pakistan. He said we are fighting for certain rights. We are fighting for certain principles but not as people to leave this country. Organising the Muslims in the same way my husband [later did].

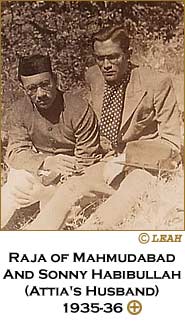

He [Ali Bahadur Haibullah 1909-1982] had gone from here and had been there just a few years. Two years after he married me [1933] and he was a very young man. He had been brought up here [in England] completely. He had a very bad accident and he lost the use of half of his left hand in tiger shoot with Raja Sahib Mahmudabad. Now Raja Mahmudabad, the young man, was at that time, as you must have heard, [full of] zest in his support of the Muslim League. In fact, had he not put all his money into it, there would have been no movement in U.P. which ultimately founded Pakistan in a way. People forget him and forget his role. This was a remarkable man. Now, as a very young man, he and my husband became close to each other like brothers because when he nearly died after this accident, as it had happened with Raja Sahib during the shoot, they got closer. Raja Sahib was distantly related to me from my mother's side. But they became very close and they were like blood brothers. My husband joined him in the Muslim League but joined him completely and we would have these arguments because I was at that time involved with thinking about the Spanish Civil War, what was happening in Germany and seeing him in a uniform, upset me tremendously because he was in the Muslim [League] National Guard, was a part of that. I said "how can you possibly?" To me everybody in a uniform who is not in the army is like those [Nazi] storm troopers. Q: What I am trying to ask is that, for those people who chose the Muslim League versus people like yourself who were Indian Nationalists, do you think it was a matter of choice? Simply human beings that wanted to chose a certain area to support, or was there a sense of genuine grievance? AH:Well in the sense that I do accept that they felt [grievances]. My husband, for example said, he was one of those three or four young men who in 1940 voted against the Pakistan Resolution [demanding a separate homeland for Muslims] because he believed, we must organise and [first] become strong within ourselves against any force that will try and make, as he used to say, the Muslims like they became in Spain " hewers of wood, drawers of water. 6. United Province [U.P.] Muslims  ATTIA HOSEIN (AH): Now the difference between him [husband Ali Bahadur] and me, influenced by the Left, which later always kept changing its hue, was this: that perhaps totally idealistic and also because by now I had graduated in Politics and Economics, I said it doesn't make sense, you cannot talk of religion as the basis of a nation. It can not be, it is not logical, and it is not historical. If, I as a Muslim am supposed to be part of a nation, I should be in Arabia. Why I am not there? Why do they [the Arabs] not consider us one of them, if only Islam matters? Other points of view, yes, that now you are going to a have a democratic process and what is going to happen is this that somebody [the Hindus] will outvote me by sheer numbers and that is what you people are frightened of. Now, I am not a genius, of course we must be in a group, of course, I was influenced by the other Muslim thought, that was there.

ATTIA HOSEIN (AH): Now the difference between him [husband Ali Bahadur] and me, influenced by the Left, which later always kept changing its hue, was this: that perhaps totally idealistic and also because by now I had graduated in Politics and Economics, I said it doesn't make sense, you cannot talk of religion as the basis of a nation. It can not be, it is not logical, and it is not historical. If, I as a Muslim am supposed to be part of a nation, I should be in Arabia. Why I am not there? Why do they [the Arabs] not consider us one of them, if only Islam matters? Other points of view, yes, that now you are going to a have a democratic process and what is going to happen is this that somebody [the Hindus] will outvote me by sheer numbers and that is what you people are frightened of. Now, I am not a genius, of course we must be in a group, of course, I was influenced by the other Muslim thought, that was there.

In those early provincial Cabinets before that were formed the Congress - remember there had been the split about saying that you should keep - they had come to some kind of pact, Mr. Jinnah and the Congress people and it was all broken because of Nehru's saying mass appeal, that sort of thing happened. The mistakes that were made. But a person like me as I say, I am not perhaps a person you should take as an example of anything except someone who believed with all my heart that you can not, you can not, found a nation on religion.

In those early provincial Cabinets before that were formed the Congress - remember there had been the split about saying that you should keep - they had come to some kind of pact, Mr. Jinnah and the Congress people and it was all broken because of Nehru's saying mass appeal, that sort of thing happened. The mistakes that were made. But a person like me as I say, I am not perhaps a person you should take as an example of anything except someone who believed with all my heart that you can not, you can not, found a nation on religion.

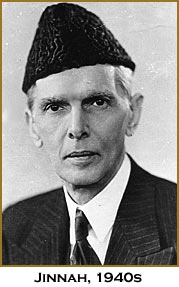

Also I said, what happens to everybody who is here [in India]? I asked that question to Mr. Jinnah. I had the audacity to ask him that. As I say to you, he was kind to me, he used to listen to me, and I said what about the Muslims in the minority provinces? The majority provinces are fine wherever they are already, what about us in U.P.? He said sacrifices have to be made for a bigger cause and I said sacrifices you know, sacrificing the likes of me, any number of people, why do politicians talk in terms of abstractions? You see, I felt that. I said to my husband, you talk here, as you talk, you talk with every good intention, you have not lost any friends, we are still living our lives. I have heard when I sit amongst the people, I would go and sit with the servants to talk to them about it. [Urdu] Haan To Yeh Ho Ga, Keh Jub Hum Niklayn Gay Hum Aur Kalma Parhany Gay Aur Bandook Chiliye Jaye Gi, Humara Par To Koi Assar Hey Nehni Ho Ga [When we leave here, this will ahppen, that we recite the Kalma (Muslim prayer), and when they shoot at us, we will be invincible] . I said, you see what that means? Do you understand what you are saying? You don't know what you are tapping into, what emotions? Q: But you thought they were sincere in their intent? AH: Some of them. People like Mahmudabad certainly, absolutely, he really felt that there is a prejudice but all this prejudice did not matter when everybody could be going towards a common purpose. But when you say that I am going to count heads, and whoever gets the most votes is going to rule over me - then that was the whole basis of the Muslim League's success. That is finally when I would say anything, let us say I can't remember all my conversations I wish I had immediately recorded them as they were. I used to ask him these questions and he said to me once, when I said, Please Mr. Jinnah, please tell me something, why is it that you don't accept the Cabinet Mission Plan [which sought to prevent the partition of India in 1945] ? For example? And then he said to me, you know that you have got to understand young woman, what about the center if it has great power? I mean the answer was always logical in terms of a political point of view. To me there was no logic in any point of view that was not human because I felt it is not true that anybody will feel that it is a nation only because it is my religion because there will be lakhs [hundreds of thousands] left behind [in India]. And what is their position, how do you mean 'sacrificed', to whom, and why? Later on after it had happened [August 15, 1947] a very dear friend of mine was the Chief Secretary in U.P., and he said to me, 'now think about it for a minute. I had to give orders to shoot if there is a riot. I am a Hindu. Where are all those leaders of the Muslims? Why are they sitting across the border [in Pakistan] when this is happening? And I have to shoot Hindus.' Now that may be that maybe that something in my head as in the heads of many of us young people and older people, when I told people that whatever is being left to one's dragon's teeth of are you sowing of hate - and now look what are we being left to? - and now look at it, the crop has grown and is visible. 7. Why Pakistan?  QUESTION: Let us jump forward for a second, looking back at it from today. Let us say there were a lot of problems at that time in the creation of Pakistan. But today what seems to be happening in India, this right-wing Hindu push, does that in any way justify Pakistan retrospectively or not?

QUESTION: Let us jump forward for a second, looking back at it from today. Let us say there were a lot of problems at that time in the creation of Pakistan. But today what seems to be happening in India, this right-wing Hindu push, does that in any way justify Pakistan retrospectively or not?

ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): No. Because it is because there was that [a separate Pakistan] they can turn on us and say, you have got your homeland, go to it. You made it and who are you here now? Why, you as a minority. The worst of them can say: why are you as a minority trying to get any special privileges. They talk of the vote bank. Ultimately, let us face it in the West. You are seeing it now in the new imperialism that it is that, that matters who has the power in their hands? Why are people fighting for religion?  I mean, I believe in the sincerity of the Quaid [Mohammed Ali Jinnah], right, because I thought he was an honest and sincere man. But I believed he was blinkered. I, who really respected him and was fond of him, and because he was kind to me. I think he didn't know history enough. What was happening in the Muslim world any way? What had happened that could not teach us a lesson? That is what I feel, that the people who pushed it were not believers in religion anyway, and to say it was not founded on religion, is not true, because the cry was 'slam in danger.'

I mean, I believe in the sincerity of the Quaid [Mohammed Ali Jinnah], right, because I thought he was an honest and sincere man. But I believed he was blinkered. I, who really respected him and was fond of him, and because he was kind to me. I think he didn't know history enough. What was happening in the Muslim world any way? What had happened that could not teach us a lesson? That is what I feel, that the people who pushed it were not believers in religion anyway, and to say it was not founded on religion, is not true, because the cry was 'slam in danger.'

Q: Some people would argue that that cry of 'Islam is in danger' actually represented 'your economic position is in danger?' AH: Why it is the economic position in danger? Because the economic position could not be improved by going somewhere else. The people, who left by the way and took their wealth with them, were people already rich in India, the Ismailis and the trading people. Q: Well, what I mean by middle class, lets say a Punjabi, lower middle class family like my father's family. They would be educated. They would try and enter the Magistrate [courts] or Civil Service, whatever, and they would see 70 - 80 per cent of the employees were Hindus and they would feel that they could never move up. AH: They could if they thought to move up as some did. RightŠ.. People did. But if you leave the people behind, by what right do you then claim that all Muslims are your friends in India? In the sense that every time any thing happened or went wrong, they would raise a clamor in Pakistan. I said that to Arshad [when he was Foreign Minister. Arshad what rights have you? You are passing a death sentence on them, are you going there to help them? Who are they to you now? Nothing. But I would like to know whom the homeland was being made for? For the people who were already there, the Punjabi Muslims, the Pathans, Sindhi or who? Q: The traditional story in Pakistan is that the real people who fought the hardest for Pakistan were from U.P. AH: Okay, so they were. Q: So they are the people who actually wanted this homeland whereas the Punjabis and Sindhis and Pathans say - AH: Well of course they did. That proves my point that they wanted what they could not have, they thought right. So don't talk about it as Islam and the Islamic State. Their religion is in danger? No. But if you talk of people a middle class, leaving them, being like as D.H. Lawrence said, how beastly the bourgeois is? And leaving everybody behind. You know during my left wing days I was ashamed of being born into a Taluqdari family and for eight hundred years having been something a part of the world in that Barabanki area [U.P. area]. I am not ashamed now because looking back on it, I think we were not as evil as the people who followed, who were grabbing in the whole world. For me it has been that I feel that the real power behind all these foundations of nations or countries has been,political aims. We are watching it now. It is happening. It is happening today in the Middle East. There will be a new middle area of Iraq carved out for the same purpose. I am not prepared to believe that Pakistan was given away by the British in a generous way accepting that there will be a just division. This wasn't a just war we had just witnessed. Just now what happened to the Indian sub-continent? Weakened, with one part of it opened to one side, one great power, and one part will, therefore, open to the other great power. So for me, politically, there can be no sense in this. Yes, of course after 1947 the Muslims had to suffer more in India. It is a bigger Muslim population than in Pakistan. So what is the justification, for whom, for the benefit of few from the middle class to get rich? Q: In all honesty, the population of Pakistan and Bangladesh put together is bigger than the number of Muslims left in India. AH: The Bangladeshis, why did they have to fight [to separate from Pakistan in 1971]? Now, if it had been Islam and if it had been purely economic benefits, why would they have to fight? Because they were used by an Imperial West Pakistan. Q: But, you know it is interesting talking to Bengali, Bangladeshis whom I interview today - still they are very proud of their involvement in Pakistan in 1947, even though they didn't like being a part of Pakistan. AH: Well, what else are they going to be? Having done what they did, and then why they have that battle? Why did they have the fight [civil war of 1971]? Q: Because we dealt with them terribly. It was justified. AH: So, wait a minute. So how did that [partition in 1947] help them? Q: I think they felt that they were really caught in a Hindu economic stranglehold. AH:Well, of course, but the stranglehold was not lifted by a partition. In fact, the stranglehold became worse. East Bengal and West Bengal complemented each other. Raw material, one side somebody developing an industry, the other side. They are the poorest nation now. Right? Q: Right. AH: All accounts and history have proved that 'yes,' there is a logic in history that the fight for unity should have won against all odds, not the fight for disunity. That is what I am trying to say, that the same sacrifices, the same thing. My friend [U.P. Chief Secretary] then said to me 'Where are all great leaders? Where they have gone? When I have to do the shooting on my own, co-religionists? I said, the English said that. But you have had wars between sovereign countries [India and Pakistan in 1948, 1965 and 1971]. Is that better or worse than rioting? No, there was no great, unified structure in that subcontinent before the British made it happen. But once it was there, had there not been this fissiparous [secessionist] movement and the same strength, as I said, put into peace, we wouldn't have had these tragedies of today. All right, I will forget all that happened, politically, economically, and the middle class has become [richer]. Yes, my own relatives are very rich in Pakistan. Most of those of us who were great feudals, what have you now? Finished, because it is a world for business. Certainly in Pakistan there were no land reforms like they were in India, which ruined our [the feudal] lot. But think about the alternatives. We are now seeing in actual fact history repeating itself on a huge terrible scale in the Middle East. What the search for power, the search for economics can do when human beings are forgotten, when it's abstractions, when we talk of statistics, when we talked of and never think that there is a living creature at the other end. You see, I am sure there must have been many many, like I was then, believing in a new world and that new world could not think of a world that could only be based on hate and violence. After all think of the great Muslims That then did emerge from that time. I mean, Rafi Ahmad Kidwai [relative of her father's family and Congress Party leader] was a remarkable man. An absolutely remarkable man who lived with nothing, gave everything he had away, saved so many lives during that time. Q: Why did so many of these U.P. Muslims from your class and background go to Pakistan? AH: Because of getting a better life, that is what I am trying to say. It is a search for a better life. Say that to me and I will say 'yes'. But don't talk about Islam and religion. 8. To England  ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): Of course, if I [were to] get a job in America that pays more - my first son has had to go [to the US]. He had a play on here at one of the theatres here, the Greenwich Theatre, and it didn't come into the Westend because you know there is a shortage of money and certain people won't back certain intellectual kind of plays. This was one of Christopher Isherwood's books made into a play.

ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): Of course, if I [were to] get a job in America that pays more - my first son has had to go [to the US]. He had a play on here at one of the theatres here, the Greenwich Theatre, and it didn't come into the Westend because you know there is a shortage of money and certain people won't back certain intellectual kind of plays. This was one of Christopher Isherwood's books made into a play.It had every success critically but didn't come in. He wanted to work here, he who was the first Indian-born to be in the BBC, the youngest after leaving Cambridge in the Slate [School of Art], didn't get work here. It is not easy for anybody still with the name that he has now - Hussein and - let us face it, color. When he started, and when my daughter tried to make something here, there weren't all these million Asians here. We were a rare breed, sort of weirdoes. He made a name for himself and David Lean said that he has to be twice as good as us to be where Waris is [son Waris Hussein, is now a film maker in the US; daughter Shama Habibullah, also a film maker, chose to live and work in India]. So he had to go to America, to work and he has gone and when he was going he was down-hearted because he wanted to do something here and he said it is like prostituting oneself to earn a living. Well I am not saying those people [who went to Pakistan] were prostituting themselves; but they really believed they were going to a homeland. They really believed it. But alas it was not our homeland like Israelis because already over there [in Pakistan] were entrenched interests. So let us face the politics and economics of history. QUESTION No. they haven't really found a place for themselves except for the city of Karachi. AH: Of course not. I chose to break my life apart. My whole private life going to pieces by staying here when my husband went as Textile Commissioner to Pakistan [in 1948 Ali Bahadur Habibullah was seconded to Pakistan by the Govt of India to help with reparations and reorganisation but did not opt for Pakistan]. I wouldn't do it again. I have learnt since. I would think of my material prospects, and I would think of security and emotional security because once one is in exile, one is emotionally in exile. As I said, the Quaid [Jinnah] could be nice to me and could understand me. To the last day before I left for England, shortly before that when we were lunching with him, I was sitting near him. He used to be nice to me and it was these great chauvinist, nationalist Pakistanis who didn't want me around at one time. Well, I loved Pakistan as a country, why shouldn't I have? When I was with the BBC, at that time it was called the 'Urdu Service' and not the 'Pakistan Service.' I was amongst the first over there to introduce certain things and to be their great Shakespearean actress and all the rest of it in Urdu because I happened to speak that language better than I am afraid Punjabis or anybody could. Shakespeare sounded better when he was spoken correctly, with the 'Sheen - Kaf' [high-brow Urdu] correct. I had to leave that work, because in the Pakistan High Commission there was an interval when amongst my friends, nobody was the High Commissioner and they said that I was amongst those who was talking against Pakistan and I went and my pride was so hurt that we would sit in the canteen and discuss it. But when the head of that service, who is a retired chap from the British Imperial Police in Pakistan, in the Punjab, said to me, why are you now not prepared to work on our terms which were weekly sort of things when I had contracts for three months, I said I refuse to. He said members of our Parliament come and broadcast, I said I don't. But I want to tell you that why would I sit and talk against Pakistan? Because I have my own closest relations there. I go there. I have friends there. I can not talk against it. It hurt so much because I had no other job. I was not qualified, I just happened to be a naturally good broadcaster. I was left without work until one day Feroz Bhai [Sir Feroze Khan Noon] came here. He was Foreign Minister and somebody else came here to see me and said how you are getting on and I said I getting on where? Your High Commission [interfered], I said. High Commission, what for [he asked]? Then they [the BBC] asked me to go back and afterwards this very same man [from the High Commission] said to me, oh I didn't know you knew the President so well. I said did that make a difference to you? Did I have to tell you who I was? Now I'll tell you that there were people sitting with me working in that room and if they had come in Lucknow to my servants' door, I would have said kick them out. But that is not what I worked for, I loved what I was doing. Q: So tell me how you landed up in Britain? AH: How? I just told you that I made an idealistic, stupid gesture that I will not go there [to Pakistan] in 1947 when my husband was in the Indian High Commission. When this division came - he was not Pakistani because we had British passports - but he accepted the job of Textile Commissioner and went to Pakistan. Sonny and I went to a reception and the women who were with me all this time in the Indian High Commission turned their backs on me. Because they thought I was with the Pakistani High Commission, and the Pakistanis were talking against India. Suddenly, this happens overnight, talking, but I said if I go with you I will never be able to say those things. I can't, I will sit here dumb, I would not be able to say that. I can't abuse the country I love [India]. I was born there and brought up there. So, neutral thinking then, when this country [England] also was different from what it is today, when there were not the same material values, when I thought that certain fundamental human values are still in this country which were not in their imperial outposts but here. Well, I said my children are being educated here, I will stay here. So he [Sonny] could not, poor chap send me money. He could only send it for their education. And I accepted that. I am not saying I was doing a great sacrificial act. It did me a damn lot of good. I couldn't boil an egg. I couldn't put the kettle to boil. I can now do everything, and I can be a very good charwoman or anything you want me to be. I even wrote. Like I had not written before because I had to, it had to come out. So I am grateful for that. I love my friends, I love my people. I say don't talk to me now of the whys and where fors of it. Now I am an old woman who merely believes in human dignity, which is being rapidly destroyed. 10. Sunlight on a Broken Column, 1961

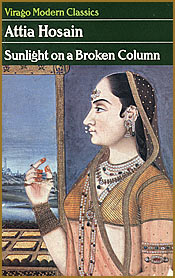

I was also, as I say, by now suffering deeply from this homesickness. I did go back in 1951 to India for recorded stuff and I went back for a month or six weeks because I had begun to lose hair which falls out with nervousness and unhappiness and the specialist said this "why she is here?" She is obviously a very unhappy person here [in England]. Well, so I came back cured and full of thoughts again and I began to realise I had to write that other book that I had promised Chatto's - not that I did the second and third. But I sat down to write that one [Sunlight on a Broken Column]. I' work and then I'd go off and sit in the country where I had a friend and stayed with her and she looked after me and shoved the food near the door and I'd go on. Then there'd be a gap because I couldn't go on then. Then I'd pick it up. In the strangest places that book was written. In Rahimyar Khan [Bahawalpur district, Punjab province, Pakistan], which was then like a wild-west outpost. QUESTION: Still is. AH: Is it? With all those people, tribesmen sitting near that railway station so that I'd get off and feel why haven't I got a burqa on? But it was good for me because I would be alone and fed and I wrote some there and it didn't go on. Then I didn't know what on earth to do with myself, I said, oh enough, I can't write and that is the end of it. If I could write a short story but what is this novel? I went then to stay with my friend, the one I told you, had talked to me after partition. I went to Nepal. He was Ambassador [of India to Nepal, Bhagwan Sahai] by then and when nobody would go to Nepal at that time, in 1956, I think it was or it was not it? It had just had that coup and the King took over. It was getting more and more rough. Anyway, I sat there and one day I said to him please don't come in near me, please don't expect me to come, to have a meal and just have some food sent in to my room. I've got to do something about this book. Now that I am in this place where everything was rather beautiful, to go and visit all those places not with tourists around at all. And I wrote it. Then I came back and I thought, look this is not what I wanted really to say. And I couldn't write it. And I wrote this book [Sunlight on a Broken Column] and was dissatisfied with it. But I handed it in to the agent and she was delighted and said that the person who was editing it and looking after it was Cecil Day Lewis [later poet-laureate of England]. She said, he's actually said that it is very autobiographical. It was very thick, and he thinks it is autobiographical.  I got very angry and I said, what does he mean by autobiographical? Every first novel or any novel will have to be part of oneself and people one knows, but it is not the people and it is not actually the events but it is at the same time yes. Then she said you better come and talk to him. Then I met him for the first time. He became a very dear friend later on. I got very angry and I said, what does he mean by autobiographical? Every first novel or any novel will have to be part of oneself and people one knows, but it is not the people and it is not actually the events but it is at the same time yes. Then she said you better come and talk to him. Then I met him for the first time. He became a very dear friend later on.

I said to him, I am afraid, I won't touch it now and he said, well, there are certain parts of it that I think you shouldn't have put in to it and I said that is how it was. And he said something to me that stuck in my head: but life is not art. You are writing a book. It is not how it was as you say in those terms and would you mind if you took some bits out? I said I won't touch it, it gives me nightmares. He said I am marking, I have marked some of the pages I was questioning. So I went off into the country and I sat with it and I can't tell you how much I sliced off. I am now sad that I threw it away because there might have been in it part of the political things that he couldn't have found at the time of any use to him, which I would find useful now as memory even. I just hacked it as I thought. The last chapters of it are almost as if I've condensed what I would have done in the next one because it is as if she has come back to her home after the partition. But the in between has gone out of the actual, as I say the pain of that partition for most of us who were left behind and sad to think that now [of] the ones who are there [in Pakistan]. They might be rich as they would never have been. They might have become Generals when they would have been only Lieutenants. But they have also felt the pain of not being accepted, totally, and sometimes it makes me angry when any of them questioned me from either side of that partition and say "oh you living in England what would you know?" In the first place, I know more than they do because I had to identify much more because I am challenged the whole time, my identity is. Also they do not know, that added to their pain of separation and uprooted feelings which they shouldn't have in Pakistan, they should have become part of it by now. What about us over here [in England]? You see that is the book that should have been written too and I am glad that there are young people writing. I am glad there are people like Aamir [Hussain] writing and if I can do nothing else I can't sit and write now because my concentration seems to have gone, though the ideas are there. I wish I could help each one of them to say, say to them you never stop, just go on because it will come. So that is the theme of it, the decay of the breaking up of a family in a way, when the whole background is changing. And what is going on and then coming back into that house [at the end of Sunlight on a Broken Column], into that place and feeling it. Q: I am sure you are asked this all the time, but why haven't you written a book since then? Was the book a real success? AH: I couldn't have asked for more. I got such good literary reviews, I can't tell you. I got asked after Phoenix Fled to be on television and everything. Why didn't I write because in my own personal life there were problems of a certain kind. I always say to people, there was so much the mind can bear and then it does not. My brother's death, my other deaths in the family, that kind of disruption got to me more, I mean I just felt, what I am trying to say to whom? People have said these things, said them better. Why am I being presumptuous that I should say any more. Q: Although it is still very different for you than it is for any one else, so you would always have your own story. AH: Exactly but why? I thought why? And when I read so and so has written an autobiography and somebody has written this and that. Compton MacKenzie once said to me why don't you Attia write your autobiography? I thought, why did they all write autobiographies, why does every body [write autobiography]? I loved him, that dear old man. He was quite an extraordinary man. Really a man who was a real human being, at 90 practically as young as anybody in his mind. I thought that if I write an autobiography, I would be telling the truth. Because I would be selective as I do not believe in exposing anybody else and one's life does expose other people. Very much so. So I didn't think in terms an autobiography but I certainly thought of fictionalizing certain aspects of the development that have happened since then. I am thinking. It needs to be written now because people are forgetting. People are forgetting all those things, they are forgetting that other world that I actually lived in, existed. There were people then who believed in the future. 9. Phoenix Fled, 1953

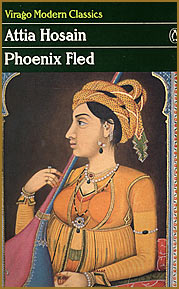

Why I remember, it's amusing, is because all of us had to write these stories and then they were read out in class. And at one point, one of my very close friends, she had written a story and I giggled at one point which was sort of romantic and sentimental. And the teacher who was an American with a very severe face, looked at me and said "And why are you laughing?" I said well, it was a bit sentimental, wasn't it? She said if there had been more sentiment in your story, it would have improved it. I always wanted to [write] and they would go round and round in my head and sometimes I would put it down and sometime I wouldn't. And they were published, some of them, in papers and magazines in India [like The Statesman or The Pioneer], in those early years. QUESTION: It was like 1930, 1940? AH: In the late, late 30s and early 40s but - Q: Were you writing in the context of Sajjad Zaheer [of the Progressive Writer's Movement] and all of that, were you reading them? AH: No. [I was] totally influenced by the West, I think, in a way but completely about my own cultural backgrounds and patterns of thought. I did not read much about Urdu literature except when I had to, because it was easier and quicker I mean when from the age of three you were brought up in an English school. True, you are taught all the rest at home but there you are and you are having to write down when you get to your college. How many books you have read when and what and you are racing through them because I could read fast, thank goodness, and I had a good memory then. I was very fond of reading as I told you. So, no it had nothing to do with them. They didn't influence me at all in my writing. They merely influenced me in my thinking politically, in no other way I don't think. I used to write as I say, these stories and then I came here and when I made this absurd decision that I would sit up in an attic and do something with my life now. At that time I hadn't yet begun at the BBC because some of the people who were originally in Lucknow and had gone to Pakistan and then come here to the BBC at that time thought I was one of those [snobs] 'Oh there she came from that big house and you know it is a kind of hobby she wants or something.' I didn't. I wanted work, I wanted some one to realize that this was not a person who was just faking. So I'd sit up there in that little room of mine which I had got inexpensively, in of those terrible, modern blocks where you don't feel at home at any time. A friend of mine had helped me as I did not know London then except as a literary place. I sat there and wrote. I had written. I was a kind of a journalist in India after I got married. I wrote for somebody here, for a little magazine that used to come out in those years, called Liliput which is a little magazine, which had all kinds of stories and all sorts of things. Rather a cult magazine, as it became. I don't know why I wrote that story ['After the Storm'], I think, to earn a little money because it was published in a magazine here. A friend of mine said that is a good story why don't you sit and write. I said how can I? Well I sat and it was days of rationing. And this kind friend [William Rawlinson, whose own family had been refugees from Nazi-occupied Lithuania, finding shelter first in Bombay before going to England and knew Ali Bahadur when he was Supply Commissioner, Govt of India in the Second World War] would bring me my bread and milk or whatever and I'd be sitting there writing this, and walking to the BBC and come back walking along the road and stories would keep coming in my head. I think I was unhappy, lonely, felt terribly home sick. My children, poor little things, had been put in boarding and it was altogether misery, I think, that made me write. And I wrote those stories and that is it. And this very friend then said and I have never, never stopped, being grateful. Whenever I ring him and his wife, I always say that you remain special because of what was done. He took it. Had it all typed properly and everything, all this collection, there were more stories than came out in Phoenix Fled . He said why don't you take it to your friend Lord Dunsany. Now Lord Dunsany was the old writer. Old gentleman, eccentric wonderful man. I showed them to him. I used to be very apprehensive about showing anything I wrote. He said now these are good enough to send to an agent. He sent them to his agent but his agent didn't think that they could be published. They came back to me and this other friend just took them from me. One day I got a call from somebody who became later a great friend of mine, and agent called Joyce Wiener who was then one of the top agents here and she said I want to tell you that Chatto wants to publish your whole book. The Hogarth Press wondered whether they should do it or should Chatto do it? This was Phoenix Fled and I thought I'd die. I couldn't believe it. I couldn't have dreamt of it. So they chose from the collection. Q: Were those stories trying to deal with partition in any way? AH: They were more - Well the first one, in a way you can see that it is the partition. There is one about a little girl after the storm. It could be that or it could be a riot. But it is about violence. Not all of them were about that [partition] but these two definitely have that hint of it. 11. Being Muslim  ATTIA HOSAIN: Here are people still but poor things they are fighting against bigger forces each day. I mean, this Gulf War [of 1990-91] devastated me. I was literally ill. And then what also made me feel angry was that every time anybody would question one, it was as if, you are Muslim, must have a different point of view for me. You, Hosain, must be related to Saddam [Hussein]. That attitude lying behind every question.

ATTIA HOSAIN: Here are people still but poor things they are fighting against bigger forces each day. I mean, this Gulf War [of 1990-91] devastated me. I was literally ill. And then what also made me feel angry was that every time anybody would question one, it was as if, you are Muslim, must have a different point of view for me. You, Hosain, must be related to Saddam [Hussein]. That attitude lying behind every question.So it had made one angry and also I am still after all a political animal, I can't ever get away from that. So that I grew up fighting an imperialism, that was always rather civilized. Yes, it murdered people in 1942. It did all kinds of things, well all rulers do, and it was my duty to fight it if it did that. But at the same time there were people whom one could sit and talk to and share certain ideas, who were here in their fight for their own democracy and their own liberties. Now who am I to talk to? The ones, poor things who are the ones that shared one's own ideas like the people who were anti-war, and such. All those people were being pushed into the background all the time. They could say it but the minute one opened ones mouth, one was reminded of Bradford Muslims doing this or that and nobody is asking me what I think of them, or whether they and I could confront each other and talk of the same religion and say what religion are you talking about? I am thinking of a religion that taught me that it's very name, what its called, means peace. You see, so people like me are dinosaurs. Q: But isn't it ironic that you left India in a way because you didn't want this Muslim identity thrust upon you, you've come to England and - AH: And it is thrust on me every day. Now I say to them before they can say anything to me, I say 'yes'. I am, and proud of it and now I'll give you a little lecture and tell you why you are not a Christian, why I am a Christian and you are not. When I say I don't believe in war, I am a Christian. I am a Muslim when I say if you turn on me and attack me and I have not attacked you, I would defend myself and add to you that my God is Rehman-o-Rahim [Beneficent and Merciful]. But you are saying that, and I am saying what Christ told you which is he never questioned any sinner, he never accepted any form of violence. He died because he did not - but he did have one episode of violence if you call it that - that from the temple he turned out the moneylenders and you do not, you welcomed them, so how are you Christian? Q: Well, that certainly is rhetorically very good. AH: Isn't it? 12. India  QUESTION: What you think the future of India is? Looking ahead for South Asia in general?

QUESTION: What you think the future of India is? Looking ahead for South Asia in general?

ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): I am very sad. I am these days frightened and sad for what is happening there. Q: Do you think it might disintegrate as a state? AH: I doubt that. I doubt they will do that. This is what people have been saying for a long time. One of my Pakistani friends, who is High Commissioner here, was talking to and said that any day now it is going to fall apart. It didn't. It will not in that sense but I think what might happen is that it will have a looser structure. More power in the states, more like perhaps in the United States, I don't know. What I am at the moment frightened is, the right-wing and its appeal to the lowest, basest instincts, which are historically not true, which is even for the Hindu religion not true but appeals to a people who can say who the hell are these Muslims? Right. Why are they here to be given most favoured minority status. They have got Pakistan Let them get out and go there. Q: I think that seems to be the ultimate goal right-wing aim, to send the Muslims to Pakistan? AH: Of course, they can't kill a hundred and ten million. Q: But Pakistan can't accept them either. AH: Pakistan, excuse me, I was told by somebody very important in 1948, end of 47 or 48, that there was - well, I will be told I am a liar, but I didn't say it. I was told by somebody who was there - that if more people come [emigrate from India to Pakistan], they have to be kept out even if they have to be shot. My friends, my dear Pathan friends would sometimes say to me, why did they all come? Didn't they have a place of their own? Right. Those Tiliars said the Punjabis. Those "Kerra Makoras," [fleas] they said in my presence in a Minister's house just before those vital elections [of 1970 that led to the break-up of Pakistan and Bangladesh], those Kerra Makoras and why do they talk? I mean if they would only think of telling of doing on certain points to us. Mujib-ur -Rehman [the founder of Bangladesh] would go on about something and I, the stranger from outside, with my darling friends around me said, but listen who are they and who are us? I thought you are all Pakistanis. No, the despair in my heart is this. That for me when you say, what do I feel about being called a Muslim, I am proud, I am a Muslim. But to me Islam has always meant that. A very sensible, logical way of making a human being, an individual with justice behind and peace is the word. Will any one contradict me on that point, it is Islam. Assalamo Allaiqum what on earth is this Assalamao Allaiqum? I don't say it because I am not a Punjabi, so I still say Tasleem and Adaab and all that [typical polite U.P. Muslim greetings], but it is the same thing. I can not understand it so. I am no use, I am a dinosaur, as I told you I belong to a world that's gone. Q: Did people of your type find a secure place in India after independence or not? AH: They have lived there. Some of my nephews have never been to Pakistan. Q: And they found a home, which is satisfying? AH: In the sense that that is their home. People do not leave their home and their little two feet of land or six feet to be buried in unless they have to. Nobody does. Q: Very difficult thing to do. AH: They have remained. They have not gone. My brother-in-law, my sister's husband was in the Civil Service, ICS. They were all given a choice whether to go or to come, I mean to go there [to Pakistan] or to stay [in India]. My brother-in-law was Collector in Benaras in 1947, think of that, of what it meant? Right. And yet when my sister, now when she was remembering those days - my brother-in-law, the stress on him, and he died of a heart attack. My sister was relating something. In those days she had to work amongst the refugees who came from across the border and were there and you can imagine the hate filled atmosphere. There was a Muslim woman walking around amongst them. By the time that she was about to leave and her husband had died, they were the ones who said that their whole life had been changed in their attitude because of her, because she was the one who was constantly there and constantly helping. Yes, I have any number - most of my closest relations are still there. Of course, they don't feel totally secure now for their lives, but then [who is safe?]. 13. Pakistan  ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): I am told that in Karachi there are lots of people with arms going around and people don't feel secure from robbery and theft. So that is another matter. Here there is hate. But the hate has been in general.

ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): I am told that in Karachi there are lots of people with arms going around and people don't feel secure from robbery and theft. So that is another matter. Here there is hate. But the hate has been in general.

QUESTION: There is no security in Karachi at all [1991]. AH:You see? That is the point that people have to remember that there were people who stayed back and people have to remember that when they talk of a majority voting in any way to go for Pakistan, it isn't true. There was a limited vote. That was not universal franchise in that same way as later. Q: That is true. I would say though in the provinces - Punjab, Sindh -  AH: Punjab and Sindh already [were Muslim majority provinces], why should they have worried? They were there and [bigger] in their numbers.

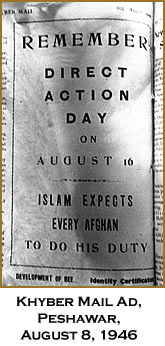

AH: Punjab and Sindh already [were Muslim majority provinces], why should they have worried? They were there and [bigger] in their numbers.I mean, we are talking now of an important minority province called U.P. Right. And that area, of course, in the North West Frontier Province [NWFP] they didn't vote. If the Pathans could have followed Badshah Khan [Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan] the way they did [for Indian nationalism], that was the miracle. And I remember when I went in 1940 and my mother-in-law said to Dr. Khan Sahib [Ghaffar Khan's brother and leading nationalist Indian pathan politician, later NWFP Chief Minister] why they were not with the Muslim League. He says, why? For what reason? What are we losing or what they [the Muslim League] are [offering]? Why you are asking me? It is logical.  But the people who had to gain anything were in the minority provinces. They thought they were gaining something. They were going to this new country. They were going to a place where they would be safe. They were going to a place where they would have every thing. But the people who had to gain anything were in the minority provinces. They thought they were gaining something. They were going to this new country. They were going to a place where they would be safe. They were going to a place where they would have every thing.