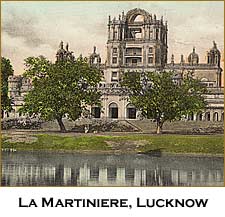

2. Two Streams of Thought  QUESTION: From childhood? QUESTION: From childhood?(AH): Contacts with the English, I still remember, were also with those same kind of people, naturally. My father's greatest friend was an English man who owned one of the big hotels at the time. He was a barrister. He'd drive to our house with a carriage and pair [of horses], that sort of thing. He spoke the most beautiful Urdu, could recite Persian poetry as everybody did because the classical poetry was always with Persian background. At the same time [I went] to a school which was one of those English schools in Lucknow, the "Martiniere". Q: Oh really, I have seen pictures of the building.  AH: Right. Very few Indian girls went to it because it was meant to be [for Europeans]. [General] Claude Martin [who served the feudal rulers of Lucknow] had left money for educating the domiciled Europeans and the Anglo-Indians and the poor amongst them or their people who needed education. So [he founded] these schools for boys and girls in Lucknow and Calcutta. The parent one [was] in Lyon [France] where he was born. These were really meant for that [Europeans].

AH: Right. Very few Indian girls went to it because it was meant to be [for Europeans]. [General] Claude Martin [who served the feudal rulers of Lucknow] had left money for educating the domiciled Europeans and the Anglo-Indians and the poor amongst them or their people who needed education. So [he founded] these schools for boys and girls in Lucknow and Calcutta. The parent one [was] in Lyon [France] where he was born. These were really meant for that [Europeans].

Q: Not for Indians? AH: Not really, but to get in was a very good thing because the education was very good. So I had that. And then I had at home, moulvis [religious teachers] to teach the Quran, to teach Urdu. I think it is quite unbelievable when people are now talking so much about how can a child learn so many things and how can it do this or that? But we did. Nobody became traumatic about it as far as I can remember. Q: I get the sense that for people like your father the English stream and Indian stream co-existed very well?  AH: Absolutely mixed completely, but that was part of Lucknow. I don't know if it was anywhere else because Lucknow was the centre of culture after Delhi stopped being that [in 1858]. In that town, as I grew, I did not know the difference between religion, caste, who belonged to which part of India? The people who came and settled there, in the university, in the professions of law or teaching or the Taluqdars were from every religion that I can think of, including the Kapurthala part of the family that became Christians. I grew up in a home where we did not have beef cooked, except very rarely, in case a Hindu friend came along. We had lights for Diwali [the Hindu festival of lights]. We had Holi [Hindu spring festival] when our friends came. They came to us for Eid [a Muslim holiday]. AH: Absolutely mixed completely, but that was part of Lucknow. I don't know if it was anywhere else because Lucknow was the centre of culture after Delhi stopped being that [in 1858]. In that town, as I grew, I did not know the difference between religion, caste, who belonged to which part of India? The people who came and settled there, in the university, in the professions of law or teaching or the Taluqdars were from every religion that I can think of, including the Kapurthala part of the family that became Christians. I grew up in a home where we did not have beef cooked, except very rarely, in case a Hindu friend came along. We had lights for Diwali [the Hindu festival of lights]. We had Holi [Hindu spring festival] when our friends came. They came to us for Eid [a Muslim holiday].

Lucknow was like that in those days. I know this that some of our closest Hindu friends. Perhaps we could not go into their kitchens, we could not go near them when they were eating, but it made absolutely no difference to the friendship. That was their life, our life was ours and it came together in friendship. We were together in marriages, at births, deaths, and any festivities. That is why for me all that happens now [the antagonism between Hindus and Muslims] is beyond belief. That is why I think I was already conditioned to believing that faith, in the fact that it can not be that we will be divided because of religion. I couldn't conceive of it myself. Q: It is interesting when you say that your Hindu friends, when they ate, or when they were in their kitchen, you didn't mind not being a part of that. I can understand that. People in the upper classes in general - that never bothered them. But middle class and lower middle class people, they always bring up this kind of an anecdote [to explain Hindu-Muslim tension]. AH: Right. But middle class? What did middle class mean in those early years? There was no great middle class. It did not happen even with them. It did not at that time perhaps because you are talking now much before 1947. Much before 1930 and certain later movements right? It might have infiltrated [later] with politics. That is what always started. If there was a riot, one could put it down definitely to this that somewhere or another, there has been somebody wanting to incite some kind of trouble. For that matter, for heaven sake, there were Shia-Sunni riots [between Muslims]. That would not have been caused by this Hindu-Muslim problem. Q: I understand that [Shia-Sunni riots] was a bigger problem in Lucknow. AH: In Lucknow it quite often happened, but we had relatives who were Shias. We had close relationships. Again now comes that other me that grew up to be politically conscious much more and more as time went on. I always believed that every time [there was a riot], there was a question of "divide and rule" as we thought, yet divide and rule does not mean only an outside power [Britain]. It means anybody who wants power, any ruler. > Images © The Literary Estate of Attia Hosain (LEAH) |

| |

| SOUNDS

| HOME